Flash Steam Geothermal Power Plant in Nevada. Photo courtesy Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Part II: Answering questions about geothermal energy production

When a group of geothermal energy experts, local government officials, and energy providers met earlier this month at Mt. Princeton Hot Springs event center to discuss Colorado’s energy reserves and their role in meeting Colorado’s net-zero carbon emissions goals, it was the first time in 15 years that a serious geothermal energy discussion has occurred.

It appears that a major geothermal reserve lies under Chaffee County and several other Colorado areas of similar geologic makeup, and this makes the county, and the state, ideal geothermal energy reservoirs… the catch — and where Ark Valley Voice left its readers last week: someone in Colorado must fund the deep drill testing and reservoir confirmation before the industry will invest in geothermal energy here in Chaffee County.

As to its benefits, geothermal energy supplies clean, renewable power around the clock, emits little or no greenhouse gases and takes a very small environmental footprint to develop. It also offers a low-carbon way to heat and cool buildings.

The gathering provided information — but it also fielded several audience questions that should be of interest to Chaffee County residents:

Q&A on Geothermal Energy:

Q. What is a deep-faulted basin and why is that important?

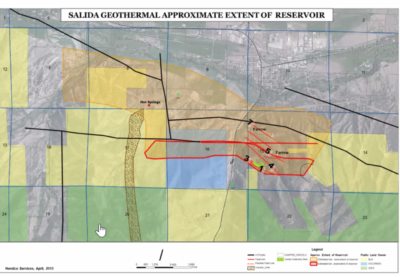

The graphics shows the Ariella extent of reservoir, or a prediction of how big and where the reservoir sits. Image Courtesy of Hank Held.

A. These are deep basins (at least 2,500 ft deep, and several go 6,000 ft deeper or more, with limited surface expressions where areas deep below ground register a 300-degree regional heat flow, driven by an aquifer source.

Some 75 of the 95 places where the deep-faulted areas in Colorado exist offer geothermal energy potential. Pagosa Springs, Glenwood Springs, Mount Princeton, the Raton Basin and the San Luis Valley, the Great Basin in Nevada are all examples of what are known as deep-faulted basins.

The Arkansas River Valley from Lake County — all the way through Chaffee, continuing through the San Louis Valley — to the edge of New Mexico apparently has the underlying geographic basis for geothermal energy.

Q. What keeps other companies from investing in this?

A. According to meeting attendees, it’s a combination of education and a bit of the “chicken or the egg”.

Colorado is still a “somewhat over-regulated state”, said Colorado Energy Office Emerging Markets Geothermal Program Manager Bryce Carter. “It becomes how do you educate on the value of geothermal energy in a place where no one is producing?”

The geothermal industry has learned a lot about deep well drilling in the past 10 to 15 years from the oil and gas industry,” he added.

To get to net zero carbon emission, we are going to need to develop geothermal energy. But someone in Colorado must fund the deep drill testing and reservoir confirmation before the industry will invest in geothermal energy in Chaffee County.

Q. What about clean energy tax credits? How are these awarded?

A. Last July, Governor Jared Polis announced $120 million in Colorado clean energy tax credits.

“All are regulated through the division of water resources,” explained Colorado Division of Water Resources Hydrology Section Manager Matt Sares .”We rank wells by type: depth and temperature — type B wells are the deeper hotter wells; we involve both the Oil and Gas Conservation Division and the Water Resources Division [in tax credits]. The last deep well we permitted – deep wells are 2,500 ft. or deeper — and applications for geothermal energy projects have to comply with the regulations we use for oil and gas deep wells.”

Asked why this is so, Sares explained that normal water wells aren’t constructed to the standards of deep oil and gas wells, “So we default to their expertise in that area.”

Q. Who regulates this and how?

A. As it turns out, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) regulates minerals. Back in 1973, Congress declared heat a mineral. In Chaffee County, just as in many other western counties, much of the lands were land grants during the time of Ulysses S. Grant, and the government kept the mineral rights on all BLM land.

Q. What about the safety of existing wells; will this impact existing wells or water quality and how can we ensure well safety and the hydrology of the valley?

A. “There is protection for those water rights,” said Sares. ‘During the application process, all water rights holders within a one-half mile radius have to be notified. No mineral extraction of any kind is allowed if it would change the quality of the water.” He added that in a few areas of the state, geothermal water has more salt — Glenwood Springs is an example.

Q. We’ve heard that the development of geothermal would be hugely disruptive and industrial-looking.

A. Not necessarily. It depends upon the type of heat pumps used to extract the heat. “We went with an air-cooling system instead of cold water to bring the geothermal extraction to the right temperature, said Mt. Princeton Geothermal Chief Scientist Fred Henderson. “They make some noise, but the area being considered for deep well drilling is on open federal land east of Mount Princeton.”

There are 50 to 100 megawatts here in Chaffee County (based upon estimates of the reservoirs ). There are ready examples of the use of geothermal heat right here in the county; Mt. Princeton Greenhouses on CR 162 in Chalk Creek Canyon heats their greenhouses with geothermal heat, and Deer Valley Dude Ranch heats its pools via geothermal water. None are intrusive to their surroundings.

Q. Given who we are (a question from Sangre de Cristo Director Dan Daly) – how can we be supportive of this effort? What benefit can we provide?

A. “Work with the USDA on rural development” said former Governor Bill Ritter. “There will be about $9.7 billion that will flow to rural CO-OPs. They need the benefit of rural thinking, of how to partner with developers here.”

“We serve 42 states and we’re in the middle of our energy transition. We’ll be 50 percent clean energy by 2030.” said Tri-State G&T CEO Duane Highley. “But we need something like this to replace the coal as we retire the coal plants. If we could tap this rift zone from here down to New Mexico it would be a game-changer. We’re watching it very closely. We want to work closely with Sangre de Cristo.”

Q. What are geothermal heat pumps (GHPs) and how do they take advantage of the earth’s heat?

A. Geothermal heat pumps (GHPs) can be used almost anywhere in the world. GHPs are drilled about 3 to 90 meters (10 to 300 feet) deep, and they extract the heat from a layer of crystalized rock some 2,500 or so feet below the surface to use to heat the home or business.

Over the last 15 to 20 years the technology has evolved and the geothermal industry has learned a lot from the oil and gas industry about how to do deep well drilling. It has shown how to do deep well drilling, which was originally considered a nuisance, because the oil they were drilling was coming out of the ground at 230 to 240 degrees.

Q. We’ve heard about the upside, what are the risks in geothermal development?

A. According to the assembled geothermal and energy experts, the greatest risk to tapping into this resource beneath our feet isn’t the ability to locate it, or safety, or even the technology necessary to tap it, it’s the lack of skilled labor. The National Energy Research Lab (NREL) is greatly concerned about the lack of trained engineers to keep up with what is expected to be a tremendous demand as the U.S. and the world attempt to meet the goals of the Paris Accord in time to stop the worst impacts of climate change.

These are only the start of the questions that are sure to arise as Colorado moves slowly toward extraction of “the energy beneath our feet.”

Recent Comments